Ruscelli's Geografia

In this collection highlight, we spend time with a humble masterpiece bridging the classical world of ancient geography and the ‘discoveries’ of the Renaissance period, 'La Geografia di Claudio Tolomeo' produced by Girolamo Ruscelli in 1561.

Its distinctive 'Orbis Descriptio' map is among the earliest double-hemisphere maps to depict the Americas, while the renowned 'Carta Marina Nuova Tavola' describes the navigational routes of mariners.

Notable for its lack of ornamentation and small scale, the book’s 65 maps and Italian text were intended to be consumed by the public rather than the wealthy elite. This copy is presented in its original cartonnage (paper) binding.

Continue reading to explore the legacy of this remarkable book!

Who was Girolamo Ruscelli?

Credit: Portrait of Girolamo Ruscelli by Niccolò Nelli (circa 1530 - 1576 or 1585) - The Art Institute of Chicago, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Ruscelli was a 16th century Venetian scholar, who was interested in cartography, mathematics, alchemy, and translation. He is known to have lived and worked in a variety of Italian cities, including Naples, Padua, and Rome.

In 1541 he became a founding member of the Humanist network, the ‘Accademia dello Sdegno’ and an influential member of one of the first scientific societies in Europe, the ‘Accademia Segreta’, or the ‘Academy of Secrets’ which was headquartered in Naples.

These societies - made up of scientists, philosophers, artists, and nobility - were established to study works of antiquity in order to learn about non-religious world views and natural history. They played an important part in shaping local culture and intellectual thought, and reviving classical learning.

Ruscelli initially earnt a living as an editor and a writer on miscellaneous topics with the publisher Plinio Pietrasanta. He edited significant Italian works such as Giovanni Boccaccio’s ‘Decameron’ and Francis Petrarch’s ‘Sonnet’. He also wrote on alchemy under the pseudonym Alessio Piemontese, outlining different techniques for making medicines and cosmetics.

Unfortunately, Ruscelli gained a reputation as a plagiarist and in 1554 he was fined 50 ducats for publishing the poem, ‘Il capitolo delle Lodi del Fuso’ without the author’s permission!

From 1555, Ruscelli stopped working with Pietrasanta, and his works – including 'La Geografia' - were subsequently printed by Vincenzo Valgrisi.

Who was Claudius Ptolemy?

Credit: Claudius Ptolemy by Theodor de Bry (1596). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Claudius Ptolemy was the original author of the ‘Geographia’. An astronomer and mathematician, he lived from c 100-170 CE.

Little is known about him, although he is thought to have been born to a noble family in Thebaid, a Greek city in present-day Egypt. He is believed to have worked in Alexandria as he made a series of astronomical observations there from 127-141 CE.

Ptolemy was a hugely influential scholar: his work was referred to for centuries after his death in both Europe and the Middle East.

He is perhaps best known for his geocentric theory of the universe, as outlined in his book the ‘Almagest’. In it, Ptolemy proposed that the Earth was the centre of the universe, orbited by the heavenly bodies. This theory remained dominant in Europe for the following 1,400 years, until 1543 when the heliocentric model described by Nicolaus Copernicus became widely accepted. Ptolemy’s other two iconic works are the ‘Tetrabiblios’, which discusses astrology, and the ‘Geographia’ itself.

The first printed edition of Ptolemy's 'Epitome of the Almagest' by Johannes Regiomontanus (1496)

The Geographia and its influence

Ptolemy wrote the ‘Geographia’ in c150 CE. It contains an extensive, detailed overview of the geographical knowledge of the known, habitable world – referred to by ancient Greek scholars as the ‘ecumene’. He gathered information for the ‘Geographia’ from a wide range of sources, including other scholars, travellers, and traders. Therefore, the book is uneven in its accuracy, but illustrates the astonishing extent to which Ptolemy and other ancient scholars knew about the world at the time.

Ptolemy’s work had a large impact on both Islamic and European cartography because it was the first time that such information had been systematically gathered and laid out. Its comprehensive geographical descriptions and understandings of the known world bridged the ancient and modern worlds and influenced scientific thought. As a result, editions of the ‘Geographia’ were reissued and reworked by mapmakers for centuries.

Ruscelli's Ptolemaic world map

It is unclear whether Ptolemy ever created maps from the data set forth in the ‘Geographia’, as none have survived. However, later scholars and publishers used the coordinates and text from the book to produce maps illustrating his knowledge. The first such maps are thought to have been created by Agathodaemon of Alexandria in c150 BC. No original manuscript has survived either: Ptolemy’s work is known through copies by monks and scribes. The earliest surviving Latin edition is Jacobus Angelus’ text from 1406.

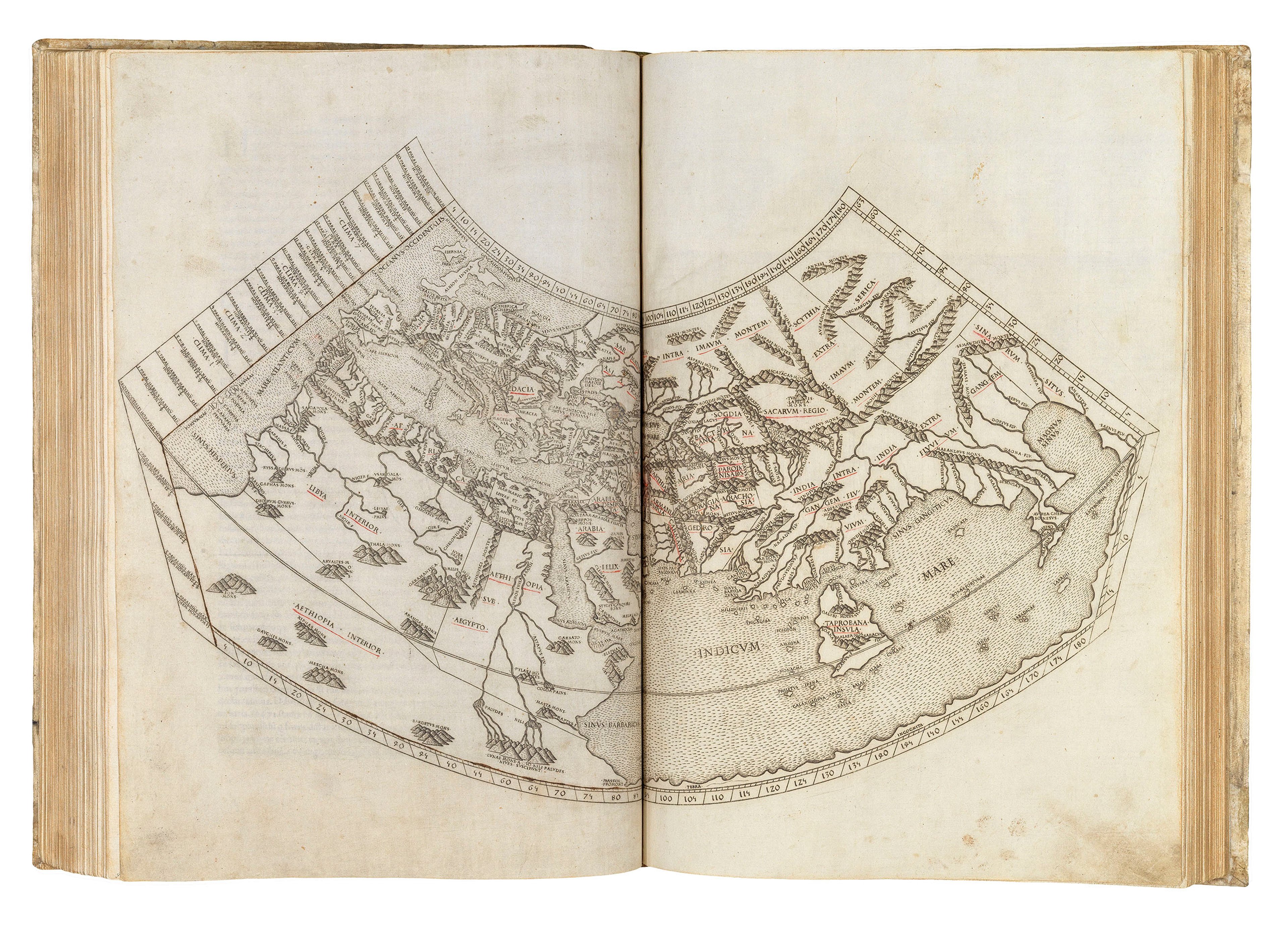

Atlases containing Ptolemy’s text alongside maps typically feature a series of regional maps drawn according to his written explanations. There are usually 10 maps of Europe, 12 maps of Asia, and 4 maps of Africa. Ruscelli’s edition is no exception. Ptolemaic maps are recognisable by their square, blocky, style. Later editions included new maps created using updated techniques and showing more extensive parts of the world – these ‘modern’ maps look very similar to most maps today. The fact that Ptolemaic maps continued to feature in these editions reflects the desire to respect tradition and honour a deeply admired, ancient scholar.

Ruscelli's 'Geographia'

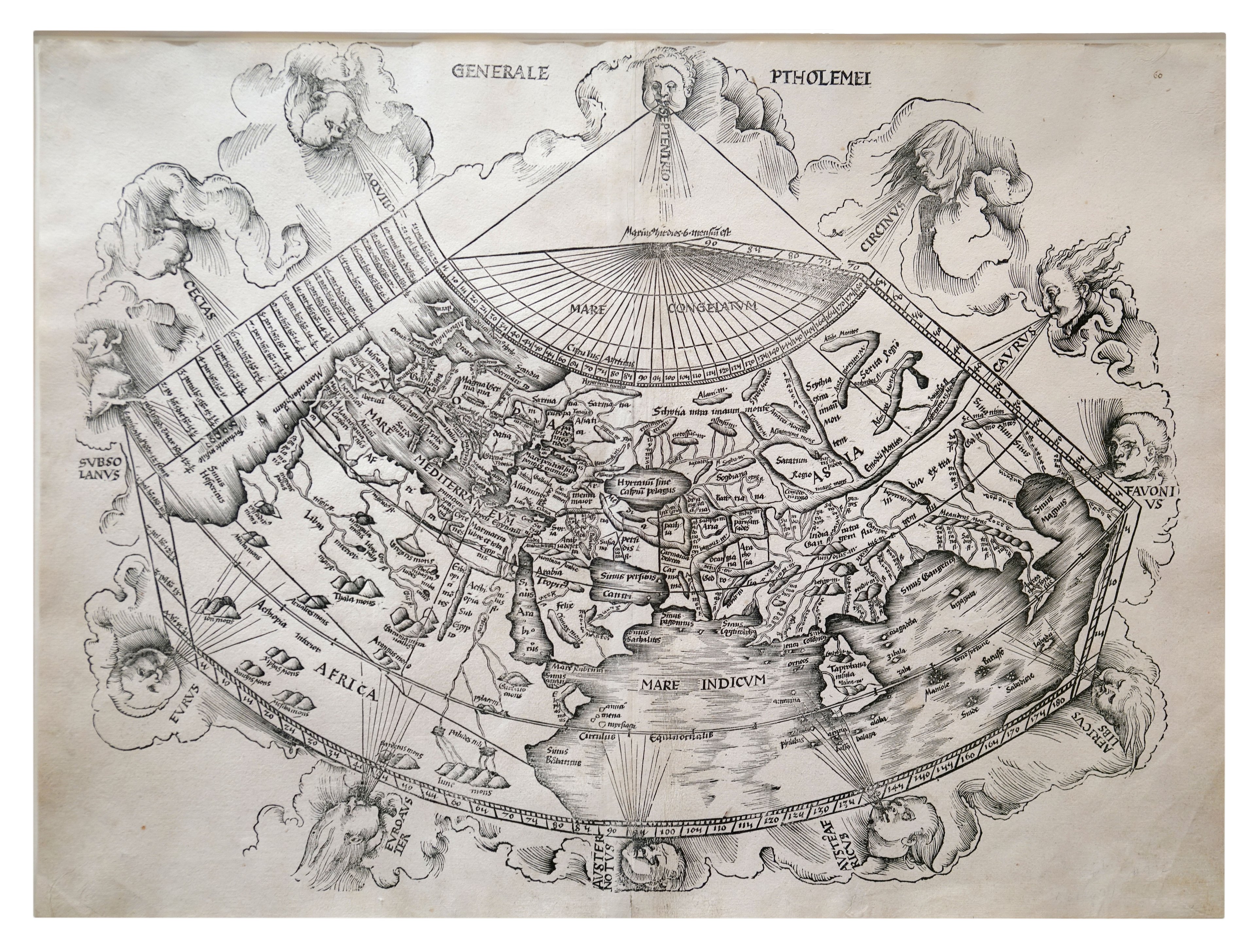

'La Geografia' was produced by Ruscelli in 1561, and printed in Venice. Following the precedent set by the likes of Francesco Berlinghieri, Johann Reger, and Martin Waldseemüller, it contains the traditional set of Ptolemaic regional maps and a world map based on Ptolemy’s second projection. Ruscelli’s edition also contains a new world hemisphere map and a marine chart, both of which are famous maps in their own right.

The text is in vernacular Italian rather than Latin, which contributed to the increasing accessibility of Ptolemy’s writing as it could be read and understood by a much broader audience. To make the book even more accessible to the general public, Ruscelli had it printed in a smaller format than the grand, leather-bound, richly coloured atlases made for wealthy patrons. It is uncoloured and apart from the maps, contains only a few illustrative diagrams of geographical instruments, optics, and projection charts.

Ptolemy's first projection

Ptolemy's second projection

The book includes 65 maps in total, which are found in the second half of the book, each framed by a simple decorative border. They are square and compact, using a grid according to Ptolemy’s system of latitude and longitude. The use of a square grid results in a degree of distortion around the edges of the map due to the curvature of the Earth being translated onto a flat scaled surface. The simple format and pared-down contents, and the exquisite way in which they were engraved, makes the maps both easy to read and very striking in a smaller-sized publication.

Ruscelli's Ptolemaic map of Europe

Ruscelli's Maps of the Modern World

Alongside the traditional set of Ptolemaic maps, Ruscelli included 37 newly engraved maps that still use Ptolemy’s projection, but are modern and describe regions of the world not covered by the original 'Geographia'.

Ruscelli’s map of the British Isles is likely based on the 1546 chart by George Lily. Due to the reduction in size, the mapmaker removed many of the chart’s details such as place names. 'La Geografia' also contains the sea charts of Scandinavia and the North Atlantic based on the voyages of the Zeno brothers, Nicolò and Antonio, who had travelled to Greenland and supposedly to the mythical island of Friesland in 1380.

Ruscelli’s ‘Geografia’ is effectively an expansion of Giacomo Gastaldi’s 1548 edition of the 'Geographia', which was the first pocket-atlas. Gastaldi’s work includes 10 maps of the Americas such as Brazil, Mexico, and Florida. His representations of the ‘New World’ - ‘discovered’ by Christopher Columbus in 1492 - reflect his attempt to reconcile the different accounts of voyagers who had travelled there.

The 'Carta Marina'

The ‘Carta Marina’ pays homage to one of the earliest printed sea charts of the world created by Gastaldi, which bears the same name, and was based upon early sixteenth century portolan charts. It highlights the rapid developments in world mapping after cartographers such as Martin Waldseemüller and Sebastian Münster, and showcases the recently ‘discovered’ New World. Gastaldi was one of the leading figures to have emerged from the ‘Lafreri School’, a group of mapmakers and engravers working in Rome and Venice who published atlases between c1540 and 1585, including Antonio Lafreri, Battista Agnese, and Antonio Salamanca. Ruscelli would have been very familiar with their work.

While recognised as a sea chart, Ruscelli’s map was not designed for practical use. The main reason for this is its very small scale, which would not have provided nearly enough information required for a sailor to use. Similarly, the rhumb lines radiating out from the centre of the map do not present realistic routes for travel; they are more of a decorative feature in the style of the portolan charts.

A striking feature of this beautiful map is the engraver’s decision to show North America extending to touch the edge of the Asian continent, alluding to the Earth’s spherical form. This map is a prime example of how commonplace cartographical myths were reproduced during this period. For example, California is rendered as a peninsula and Tierra del Fuego is depicted as a single island beneath South America. The misconception about California would later evolve to show the region as an island. From around 1620 until the beginning of the when Jesuit missionary and explorer Eusebio Francisco Kino published his map in 1726 confirming it was in fact a peninsula. The error of California as an island remained on maps until c1750!

The 'Orbis Descriptio'

This elegant and simple map is the first double hemisphere world map to be included in a European atlas. As its title states, the map describes the whole world. Here the earth is divided into the East and West, and rendered within two perfect circles. Prior to Ruscelli’s ‘Geographia’, double hemisphere projections were reserved for large-scale luxury maps, such as the stunning examples by Tramezzino which can be found in the Sunderland Collection

Like the regional maps in this 'Geographia', the double hemisphere diagramme is derived from the work of Gastaldi, in particular his 1546 and 1548 world maps on oval projections. However, it has no direct predecessor and Ruscelli’s work diverges from Gastaldi in its depiction of mountain ranges and rivers around California, and its representation of northern America extending up into the Arctic with the label ‘Hyperborei’.

As in the 'Carta Marina', America is drawn by Ruscelli as connecting to Asia via 'Terra Incognita' – unknown territories. This world map also displays various cartographical errors. For example, South America is rendered with extra curves and bulges and Ruscelli has entirely excluded the Southern continent that is present in many early maps as a counterweight to the Northern polar region. The unknown coastlines around Java and the north of the East Indies are shown speculatively in dotted lines.

We know that this map reached as far as China not long after its printing in Venice. This is partially due to the fact that Ruscelli’s atlas was affordable and was designed for wide, public consumption: more copies were thus in circulation, and could be more easily transported than a luxurious, very expensive large folio atlas.

One of the first known scholars to include images of the Renaissance world in a book was Zhang Huang 章潢 (1527–1608), a prominent scholar from the city of Nanchang. His multi-volume ‘Compendium of Diagrams and Writings’ (Tushubian 圖書編), printed shortly after his death in 1613, features two separate hemisphere maps that bear close resemblance to Ruscelli’s. They appear next to a schematic representation of the nine-layered heavens (see figure below).

CREDIT: Huang, Zhang: 涂鏡源等, 明萬曆癸丑 [41年, 1613]. Vol 23, seq. 49 and 50. HOLLIS number 990079102480203941. From the collection at the Harvard-Yenching Library Collection of the Harvard College Library, Harvard University. Public Domain.

Above, below, and within the hemispheres are impressionistic renditions of Roman letters. These seemingly meaningless scribbles illustrate how efforts were made in China by scholars such as Zhang, to understand foreign writing through the information available to them. The individual ‘letters’ in his Compendium closely match Latin script in number and placement, but were actually gleaned from an early modern Thai publication. Chinese-Thai dictionaries were in circulation at the time, and must have been consulted in the process of copying Ruscelli’s text from the original, in an effort to find meaning in a foreign script. In this instance, the images thus appear to have entered the Compendium essentially as foreign illustrations that could not be deciphered (or at least not by the author-compiler Zhang).

The inclusion of the hemisphere maps in a Chinese publication, and the method by which scholars such as Ptolemy sought to gather and interpret information from afar, are fascinating examples of how physical books – including manuscripts and atlases – have traversed great distances since early history; and how knowledge has been eagerly sought and amalgamated across cultures.

Depiction of the twelve classical windheads

Illustration of a globe

References

We are very grateful to Dr. Mario Cams and Philip Curtis, Director of The Map House, for their contributions to this article.

Ruscelli, Girolamo, William Eamon, and Francoise Paheau. The Accademia Segreta of Girolamo Ruscelli: A Sixteenth-Century. Italian Scientific Society. Isis 75, no. 2 (June 1984): 233–242.

Iacono, Antonella. Bibliografia di Girolamo Ruscelli: Le edizioni del Cinquecento. In appendice: Antonella Gregori, Saggio di censimento delle edizioni dei Secreti. Introduced by Paolo Procaccioli. Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, 2011.

Procaccioli, Paolo. “Ruscelli, Girolamo.” Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 89. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 2017.

Crouch Rare Books: "Girolamo Ruscelli"; Accessed May 1, 2025.

Ptolemy, Claudius. Geography of Claudius Ptolemy. Translated by Edward Luther Stevenson. Introduction by Joseph Fischer. Illustrated edition. New York: Cosimo Classics, 2011.

Ptolemy. Ptolemy's Geography: An Annotated Translation of the Theoretical Chapters. Translated by J. Lennart Berggren and Alexander Jones. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020.

Shalev, Zur, and Charles Burnett, eds. Ptolemy’s Geography in the Renaissance. Warburg Institute Colloquia. London: Warburg Institute, 2011.

Diller, Aubrey. "Review of Stevenson's Translation" Isis 22, no. 2 (February 1935): 533–539

Jones, Alexander Raymond. "Ptolemy"; Encyclopaedia Britannica. Last modified February 12, 2025.

Richter, Lukas. "Ptolemy."; Grove Music Online. 2001; Accessed 1 May. 2025.

Neugebauer, Otto E. A History of Ancient Mathematical Astronomy. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media, 2004.

Toomer, Gerald J. "Ptolemy (Claudius Ptolemæus)"; In Dictionary of Scientific Biography, edited by Charles Gillispie, vol. 11, 186–206. New York: Scribner; American Council of Learned Societies, 1970.