How Maps Were Made

The maps in the Sunderland Collection are exquisite, but how were they made? And how did map-making techniques change over the centuries?

Manuscripts

A manuscript refers to a writing by hand – as opposed to in print. They can be found as individual leaves, scrolls, or bound up in books. Each manuscript was entirely hand-made, and is therefore unique.

In the medieval period, manuscript pages were usually made from vellum, animal skin which had been soaked, dried, and shaped with a crescent-shaped knife called a lunellum. The pages were then sewn together in sections of folded leaves. Each page was prepared with ruled lines for the scribe to write on with a pen, typically the sharpened end of a feather. The pigment used for writing and decoration was made from ingredients such as minerals and natural dyes.

Medieval and later manuscripts often contain beautiful decorations, such as miniature scenes inside large capital letters, embellished borders, and full-page images. The expense and beauty of these illuminated manuscripts, which used coloured inks heightened in gold and silver, made them high-value commodities for elite members of society.

Producing manuscripts was time-consuming and expensive. However, they continued to be made even after cheaper and quicker methods of book production had been invented, such as the printing press. This overlap can be seen in the rubrication of early printed works.

Rubrication is a technique where ink is applied by hand to emphasise an important part of the text. A common example of this is where capital letters have been marked or embellished – sometimes very richly, using bright colours and even gold leaf. Here we see a page from Isidore of Seville's 'Etymologies', dated 1472.

For the TO map in this manuscript after William of Conches, the scribe drew the outline of the circle representing the earth and the lines separating the continents before adding in labels and colour in ink.

A very map-specific type of manuscript materials is the portolan chart. These richly decorated, detailed nautical charts were produced on vellum from the late 13th century CE, and continued to be made throughout the early modern period. Examples in The Sunderland Collection include the the Cadamosto Codex, and two portolan charts of the Mediterranean by Joan Oliva.

Another beautiful example is the the album of traditional Korean maps, from the ‘Ch'onha Chido’. In this atlas, maps have been executed in black ink on rice paper, before being coloured and then embellished with flowers. The individual maps are mounted on silk.

Woodcuts

Woodcut is a form of printing originating from 8th-century China and was used widely in the production of illustrations in Medieval and Renaissance Europe.

First, a design is carved or incised onto a block. Woodcuts are made in relief, which means that the block acts like a stamp. The parts of the design that will be left blank on the print are cut away from the block, and what is left is covered in ink. The design is then transferred onto paper (or another medium, such as cloth) by applying pressure.

Great care is required to carve a design into the woodblock. Parallel lines, called hatching, are often used to indicate shading.

An advantage of woodcut over manuscript works is its ability to be reproduced. Multiple copies of the same map or other image could be made from one block – sometimes so many times that cracks appeared and the block had to be re-cut. This made woodcut products accessible to a wider number of people.

Despite the difficulties of woodblock, they could be incredibly detailed, such as this double-cordiform world map on a polar projection by Oronce Fine.

The most important development in the print production of atlases and other books was the invention of the printing press and movable type in about 1450, by the German goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg. It revolutionised the technology of woodcut printing, making the manufacture of books and prints quicker and easier. A huge increase in book production occurred, so they were no longer only enjoyed by the social elite.

Because woodcut illustrations used the same printing technology as movable type, the printing press allowed for the mass production of printed books illustrated with woodcut prints. Examples in The Sunderland Collection include Hartmann Schedel's 'Nuremberg Chronicle' and the hybrid T-O map by Ambrosius Macrobius in his Commentary on the Dream of Scipio, 1500, as shown here.

If you look carefully at some maps, you will see that metal type was inserted onto the wood as a means of printing place names and other text. This enabled printing in two colours. It was also very helpful where a printmaker wanted to leave a cartouche or description blank, in order to update it or change the text later. In Bernadus Sylvanus’ heart-shaped world map at left for example, movable type is used for key place-names, the labels of wind-heads, climate zones, and the cardinal directions.

Woodcut maps could also be enhanced through hand-colouring with pigments made from rare ingredients. Highly valuable lapis lazuli transported from Afghanistan was used for the Ulm Ptolemy world map, printed in southern Germany in 1482.

Hand-coloured printed maps could be made less expensive through the use of colour-wash rather than pigments: the German printer Johann Reger did just that with his reissue of the Ulm map.

Woodblock printing is still used today. Highly skillful, stunning wall maps have been created - such as the dazzling "Blue China" map by Huang Qianren in 1810. This rare map covers 8 sheets of rice paper!

Engraving

Another type of printmaking technology is engraving; first using copperplate, and later on steel. Engraving is a form of intaglio print. This process is the opposite of relief printing. A sharp metal tool called a burrin is used to incise the design into the plate. Ink is then applied to it and collects into the incisions. Once the ink is wiped away from the surface, it only remains in the areas which have been cut away. The design is then pressed onto paper with a printing press.

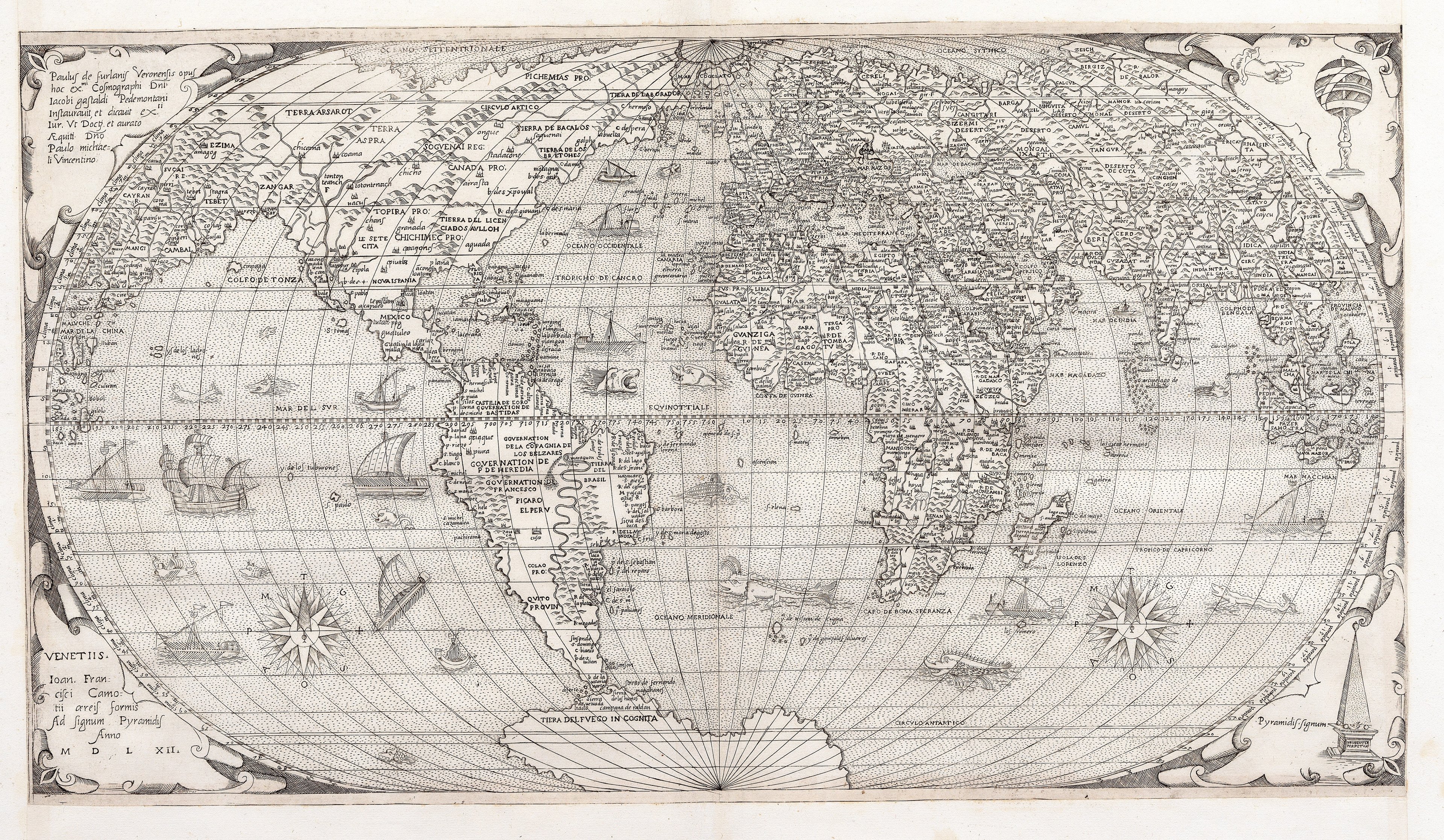

Many of the maps in The Sunderland Collection are engraved, such as the world maps by Paolo Forlani and Francesco Berlinghieri, and the Eastern and Western hemisphere maps by Michele Tramezzino.

An advantage of engraving over woodcut is that more detailed designs could be produced using the fine burrin, and copper was stronger and allowed more delicate engraving than wood. This can be seen in this early Ptolemaic map. Delicate short dashes are used across the bodies of water and mountain ranges.

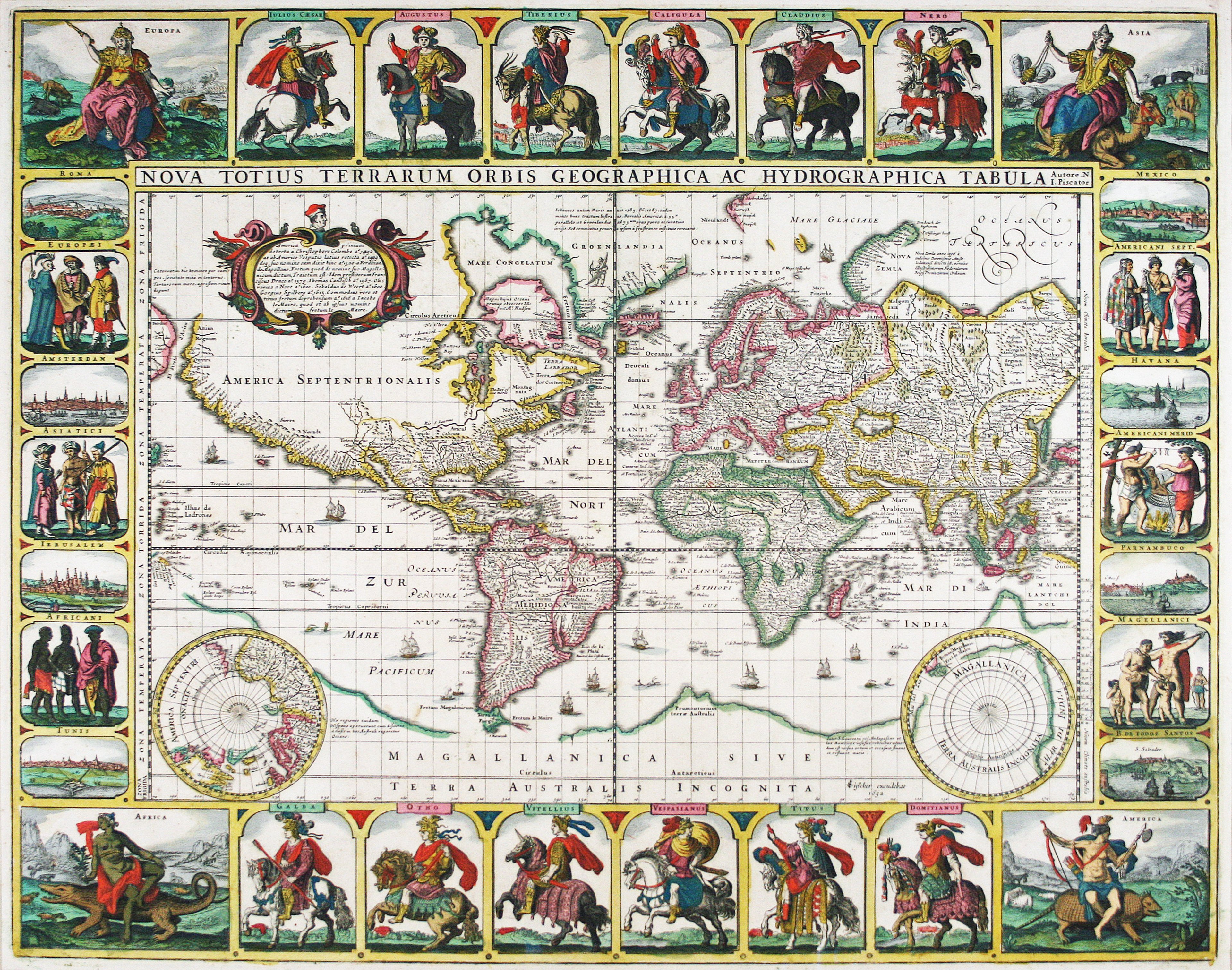

Other techniques like cross-hatching, where perpendicular lines cross over each other, was used to create the illusion of shadow and depth. More complex decorations like figural illustrations and architectural imagery could be added to engraved maps. Examples of maps that make use of the artistic potential of engraving include Giovanni Cimerlino’s heart-shaped map at left, Jodocus Hondius' "Christian Knight" map, and Athanasius Kircher’s etchings of subterranean water and fire below.

Copperplate prints could also be finely hand-coloured, making each map unique and eye-catching. Many of the hand-coloured engraved maps in the collection are particularly striking, such as Visscher’s "Twelve Caesar’s" world map.

Engraving was used to collect large numbers of maps into atlases, creating comprehensive compendiums of cartographic knowledge that could be reproduced and shared through print technology. Copper was extremely expensive, and the amount of information that could be recorded using intaglio techniques was considerable. Therefore, the plates belonging to publishers of atlases were highly coveted items.

The plates were also often used for many editions of the same popular work. In later editions, cracks literally begin to show on the printed impressions of maps. The cost of copper also meant that sometimes plates were melted down and reformed, which meant that the original engraved work has been lost, and only impressions remain.

Copperplate continued to be a medium of choice for mapmakers throughout the early modern period. Some of the later engravings in The Sunderland Collection include Pierre du Val's Trade Map, the world map from Raif Effendi's Ottoman atlas, and Jean-Baptiste Nolin's beautiful and grand wall map.