Bayer's Uranometria

Introduction

For this featured collection highlight, we invite you to join us for a spot of seventeenth century stargazing as we share a seminal work that combines ancient celestial lore and the latest astronomical discoveries: Johann Bayer’s Uranometria Omnium Asterismorum Continens Schemata (1639).

This beautiful set of charts was included in The Sunderland Collection as an example of pre-telescope astronomy, and sits in conversation with its other celestial material, some of which is discussed below.

©The Sunderland Collection

For millennia, star maps have been essential references for navigation, agriculture, religious contemplation, story-telling, and astronomical study.

Whether presented in carvings, on globes, in books, or as standalone charts, these celestial guides were crucial for helping humans to understand, catalogue, and move through our cosmos.

The earliest printed European maps of the night skies were produced in 1515 by Albrecht Dürer, Johann Stabius, and Konrad Heinfogel. Having created a woodcut terrestrial map of the world as a sphere (also 1515), Dürer and Stabius naturally followed up with its celestial counterpart.

The sheet depicting the northern hemisphere also featured the likenesses of early astronomers: Aratus, Ptolemy, Marcus Manilius, and Azophi Arabus (ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn ʿUmar al-Ṣūfī).

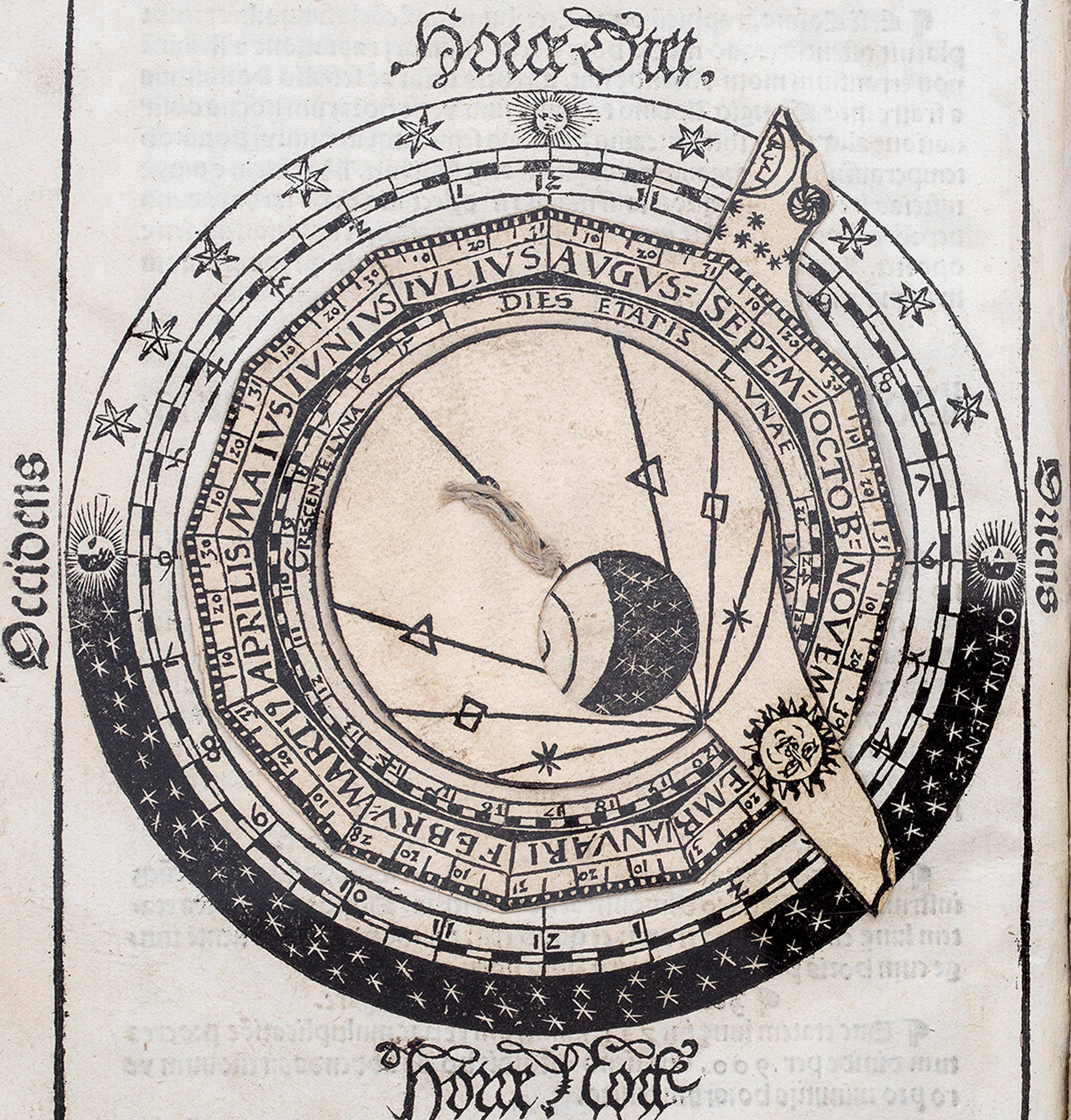

These two charts were further developed by Petrus Apianus in his iconic instrument work Astronomicum Caesarium (1540), shown below, and in the 1541 star maps of Transylvanian mapmaker and theologian Johannes Honter (1498-1549). A copy of both these works can be found in The Sunderland Collection.

The constellations depicted in Honter's charts used a radical new perspective, viewing the stars from Earth in a concave projection. They also act as a charming historical record of contemporary dress.

©The Sunderland Collection

First published in 1603, the Uranometria was one of the most elegant and influential celestial achievements of the period. Renowned for its cartographic precision and artistic beauty, the work present a comprehensive, pre-telescopic vision of the heavens. It is the first European printed atlas to plot the complete celestial sphere, showing over 2,000 stars.

Some scholars cite Bayer's work as the ‘first complete star atlas’ to be produced in Europe, although fifteen years earlier Giovanni Paulo Gallucci published Theatrum Mundi (1588), which presents fairly accurate star charts on a trapezoidal projection and uses Nicholas Copernicus’ De Revolutionibus (1543) as a guide for positioning.

Who was Johann Bayer?

Johann Bayer (1572-1625) was born in Rain, Bavaria, in southeast Germany. He studied law and philosophy at the famous University of Inglostadt in 1592, and later worked as a lawyer and the official legal advisor for the Augsburg city council. Little else is known about his life, in part because there were several eminent figures with the same name.

As well as his career in the law, and a keen interest in mathematics and archaeology, Bayer was passionate about astronomy. Through careful study, he taught himself how to observe, record and categorise the stars in the night sky.

Classical Influence, Modern Data

The Uranometria compiles Bayer's astute observations of the cosmos, merging precise stellar positions with artistic rendering of the constellations. The work does not entertain conversations about the position of the Earth and other celestial bodies within the universe, even though this was a hot topic at the time.

![This is a page from Kitāb ṣuwar al-kawākib al-thābita [Book of the Images of the Fixed Stars] (c.1000). It was written by the Persian astronomer ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn ʿUmar al-Ṣūfī, known in Europe as Azophi Arabus (903-986 BCE).](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/foan2pfl/production/82d941bca08b71811260d5a49da748ecccf4db6e-2477x2745.jpg?w=3840&q=85&auto=format)

©Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

One of the key sources of inspiration for this work was the al-Ṣūfī manuscript, Kitāb ṣuwar al-kawākib al-thābita [Book of the Images of the Fixed Stars] (c.1000). It was written by the Persian astronomer ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn ʿUmar al-Ṣūfī, known in Europe as Azophi Arabus (903-986 BCE).

![Page from ‘De le Stella Fisse’ [‘On Fixed Stars] (1540) by Alessandro Piccolomini (c1559-1620).](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/foan2pfl/production/a08defa4b007c1e4a0dd6f31c410687b1f432efe-468x600.jpg?w=3840&q=85&auto=format)

Image courtesy of The Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering & Technology.

Bayer's work also draws heavily on Regiomontanus' printed edition of Ptolemy’s Almagest (1496), a copy of which is in The Sunderland Collection.

‘De le Stella Fisse’ [‘On Fixed Stars] (1540) by Alessandro Piccolomini (c1559-1620), shown here, was another great influence. However, Piccolomini’s work did not feature a coordinate system meaning that readers could not easily or accurately locate individual stars.

The Uranometria includes a great deal of scientific data from Brahe's star catalogue of 1602, which plotted the positions of 1,005 stars. Bayer very likely also possessed a manuscript copy of Brahe’s observations of the northern hemisphere, prior to its formal publication.

In addition, Bayer may have consulted the celestial globes of Jodocus Hondius and Willem Janszoon Blaeu, and the astronomical tables of Johannes Kepler.

The illustrations of personified and anthropomorphised constellations in the Uranometria are by the Dutch painter Jacob de Gheyn II (1565-1629). De Ghyen’s etchings were highly accomplished, but not scientifically accurate. The plates in the Uranometria have been exquisitely engraved into copper by the German engraver Alexander Mair (c.1559–c.1620) after de Gheyns' etchings.

The Northern Hemisphere

The Uranometria painstakingly illustrates the 48 constellations described by Claudius Ptolemy in the Almagest, his seminal book on astronomy. The fixed positions of these stars in the northern hemisphere has been based on the work of Danish astronomer Tyco Brahe.

The Ptolemaic constellations are: Andromeda, Aquarius, Aquila, Ara, Argo Navis, Aries, Auriga, Boötes, Cancer, Canis Major, Canis Minor, Capricornus, Cassiopeia, Centaurus, Cepheus, Cetus, Corona Australis, Corona Borealis, Corvus, Crater, Cygnus, Delphinus, Draco, Equus Minor, Eridanus, Gemini, Hercules, Hydra, Leo, Lepus, Libra, Lupus, Ophiuchus, Orion, Pegasus, Perseus, Piscis Austrinus, Sagittarius, Scorpius, Serpens, Taurus, Triangulum, Ursa Major, and Ursa Minor.

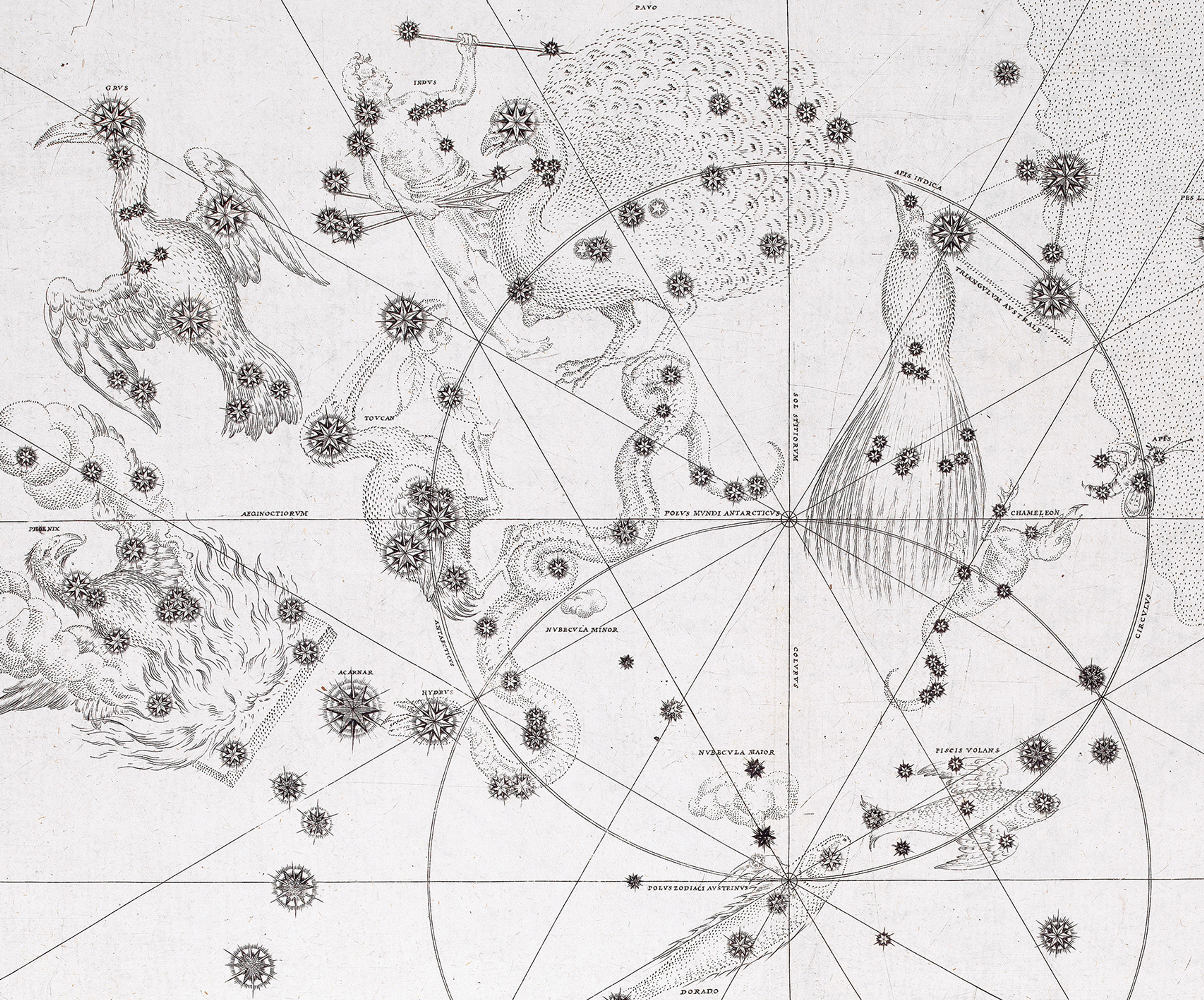

The Southern Hemisphere

Despite the necessity for up-to-date celestial charts to guide European explorers sailing across the globe from the late-fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries, maps of the southern skies remained largely blank until Uranometria’s release. It is likely that expansionist imperial powers deliberately withheld this navigational information to prevent rival empires from gaining an advantage at sea.

In this atlas, a 49th plate was included - this was one of the first European attempts at accurately depicting the stars of the southern hemisphere.

For the Southern Hemisphere, Bayer drew on Petrus Plancius’ publication for the positions of the stars in the southern skies and twelve new constellations first observed by Dutch navigators Pieter Keyser (1540–1596) and Friedrich de Houtman (1571–1627) during an exploratory voyage to the East Indies in 1595.

These new constellations were first depicted on a globe circa 1598 by Hondius. Here, you can see Bayer’s updated rendering of the southern night sky featuring the constellations: Chamaeleon, Phoenix, Triangulum australe (southern triangle), Apus (bird of paradise), Dorado (swordfish), Musca (fly), Tucana (toucan), Volans (flying fish), Grus (crane), Pavo (peacock), Hydrus (snake), and Indus (Indian).

A Lasting Impression

For this second printing of the Uranometria, its publisher Johann Görlin rectified several issues with the first edition. In particular, he removed the astronomical tables from the verso of the image plates. This not only maximised the final impression of each image plate, but made the publication more user-friendly. The tables were removed from all subsequent editions and printed as a separate star catalogue titled Explicatio characterum aeneis Uranometrias (1624).

The copy of the Uranometria in The Sunderland Collection was rebound shortly after being acquired by its original owner, so that the plates are presented vertically and thus have no gutter interrupting Bayer's delicate engravings. There is also a hand-written note in the fly-leaf, stating that this owner had a copy of the star catalogue filed in his library.

The Uranometria was revolutionary for its use of Bayer’s methodology of labelling (apparent) bright stars with Greek letters, each of which would define the ‘classes’ of magnitude, or brightness. This was also based work by Brahe and other predecessors.

The nomenclature system developed by Bayer - known as ‘Bayer letters’ - is still used by astronomers today. For example, the brightest star in the constellation Orion, Betelgeuse, is also known as Alpha (α) Orionis. According to the International Astronomical Union (IAU), this labelling has been extended to apply to about 1,300 stars. Despite issues with accuracy in Bayer's system, it would remain standard until updated nomenclature by English astronomer John Flamsteed became popular in the early eighteenth century.

The popularity of Bayer’s remarkable atlas meant that it would run into almost a dozen editions between 1603 and 1689, and would serve as a key resource for astronomers over the following 200 years.

Explore The Sunderland Collection's copy of Uranometria in brilliant detail here.

References

Kanas, Nick. 2019. 'Star Maps: History, Artistry, and Cartography'. Third Edition. Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland.

Whitfield, Peter. 2018. 'Mapping the Heavens'. London: British Library Publishing.

Huntingdon Library: ‘Uranometria’, 2022.

Warner, Deborah Jean: ‘Johann Bayer and his star atlas - reconsidered’. 1975 (Journal of the British Astronomical Association, Vol. 86, p. 53-54).

Linda Hall Library: 'Out of this World' Online Exhibition.

International Astronomical Union. ‘Naming Stars’.

Hafez, Ihsan: 'Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi and his book of the fixed stars: a journey of re-discovery' Harvard University, 2010. Extract.

Ridpath, Ian: 'Star Tales: Tycho Brahe’s great star catalogue. First true successor to the Almagest'.

Cellarius' map of the constellations in the Southern Hemisphere (1661).