djoeke van Netten

Series 3 Episode 6

Encountering Polar Bears and the Unknown with djoeke van Netten

Series 3 Episode 6

Available on all major podcast platforms: click the icons or hit 'play' to listen now.

In this episode, Jerry and Dr djoeke van Netten from the University of Amsterdam, take us to the Arctic in the late 1500s. This 'Map of the Polar Regions' (1598) depicts the attempt by Dutch navigator Willem Barentsz and his crew to reach China via the Northeast passage.

djoeke guides us through Barentsz's three missions in 1594, 1595, and 1596, which culminated in the group being stranding on Novaya Zemlya for almost a year. She illustrates the explorers' understanding of their surroundings, including their interactions with wildlife. Polar bears in particular sparked significant curiosity and concern among the Dutch travellers. djoeke reveals how these interactions not only informed the crew's survival strategies but also shaped their perceptions of the Arctic environment.

We hear how maps not only record known geography but also convey the unknown - reflecting both an acknowledgment of limits and the ambition of European exploration.

To view the map while you list, click the image below!

Willem Barentsz, Map of the Polar Regions (1598). Engraved by Baptista van Doetecum, published by Cornelis Claesz ©Barry Lawrence Rare Maps; public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

This important early map of the Northern Polar Regions was created by Willem Barentsz (1550-1597) based on his voyages, and published posthumously. The objective of his expeditions was to find a northerly route from Europe to Cathay (modern China) via the Arctic. This was a common, competitive goal shared by the Dutch Republic and other imperialistic European nations who saw enormous trade potential in the riches of East Asia.

By the time of Barentsz' journeys, were already two well-established routes: one circumnavigating the Cape of Good Hope in Africa, and the other through the Magellan Straits in South America. However, because they were controlled by the Spanish and Portuguese respectively, finding an alternative northwest or northeast passage was imperative.

Portrait of Barentsz (1883). ©Getty Research Institute. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A mapmaker by trade, Barentsz turned his hand to navigation, answering the Dutch Republic's call to try and secure a northern route to East Asia.

He hypothesised that due to the 24-hour polar day, the Arctic sea ice would have melted by the summer months leaving a navigable body of water.

Barentsz's map shows a sweeping view from the northernmost reaches of Greenland and the modern Canadian Arctic, across to the unfinished northern coastline of Russia.

You can learn more about Barentsz and his voyages here.

Radiating out from the North Pole, Barentsz peppered his map with ships, animals, and sea monsters. Three glorious compass roses point due north to orient the viewer, and further embellishments such as fine Italianate strapwork frame the title cartouche, adding to the splendour of the work.

The stipple-engraved (dotted) line on the map traces the route of Barentsz’s third, ill-fated voyage in 1596. Originating in Holland and sailing north toward the Arctic Ocean, his ships landed at T'veer Eylandt (Bear Island) before finding Het Nieuwe Land, or The New Land (modern Spitsbergen) on 17 June, 1596. The ‘discovery’ of Spitsbergen would become one of the expedition's major achievements - and this map became the first printed work to mark that territory.

After landing at Spitsbergen, Barentsz continued east to the Russian coast. En route, the crew collected meteorological and astronomical data, and corrected their navigational charts to reflect the coastline they encountered.

Barentsz and his crew reached Novaya Zemlya on 17 July 1596. This region between the Kara Sea and Bering Straits was notoriously difficult to navigate. Despite their anxious attempts to avoid becoming trapped in the surrounding ice, their ship became stranded. Thinking on their almost frost-bitten feet, the 17-strong crew used driftwood and timbers salvaged from the abandoned ship to build a log cabin in which to spend the winter.

Those with a discerning eye following djoeke and Jerry’s conversation will spot a tiny illustration of a hut on the north-eastern edge of the jagged Novaya Zemlya archipelago. This is Het Behouden Huys, or The Saved (or Safe) House.

From left: Barentsz's 'Saved House' on the map, and a view inside the House from a work by A. E.Nordenskiöld, who is credited with the first successful navigation of the Northeast Passage in 1878–80. Both public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Right: An engraved view from Gerrit de Veer’s 1598 Journal. Public domain, via World History Encyclopaedia.

The naval officer and carpenter aboard Barentsz's expedition, Gerrit De Veer, recorded events between 16 May 1596 to 1 November 1597 in a journal. His writing provides an insight into daily life and learnings on the ship, and when wintering in Novaya Zemlya. De Veer also stored valuable information about the wild inhabitants of these unknown lands, and the Dutch’s first interaction with polar bears!

One of djoeke’s research focuses is the depiction of animals on historical maps. Not only can it inform the relationship between humans and animals in different parts of the world, but it can also show the dissemination of knowledge through cartographic works.

Particularly on this map, she highlights that some of the polar bears look fierce and unwelcoming to match the hostile Arctic landscape. But in other places, they are shown as ‘cute’, suggesting that the Dutch voyagers grew fond of the creatures they shared their winter quarters with. The vignettes of whales, reindeer, and walruses shown on the map also reveal information about trade and survival in the region.

Engraving from Gerrit de Veer's journal (1598). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

During the expedition, 17 polar bears were killed: their pelts kept the crew members warm, and their fat fuelled their oil lamps.

One polar bear was to be taken back to Amsterdam partly as a specimen to study and partly as a trophy of their achievements - but after realising that it would not be safe to transport this monster home alive, they chose to end its life.

There was only one occasion where Barentsz' crew ate a polar bear. It tasted awful - which probably saved the bears from becoming extinct, and in turn, stopped the crew from getting very ill!

Gerrit de Veer was the first European to describe what is now known as Hypervitaminosis A - the toxic effect of ingesting too much vitamin A (which is found in the liver of a polar bear). This information was already understood by the Sámi and Nenet people indigenous to the northernmost parts of Scandinavia and Russia, but of course, having never met a polar bear, the Dutch were none the wiser.

After a 10-month futile wait for their ship to break free from the ice during their third and last voyage, the crew opted to return west in smaller, open-top boats. Upon their arrival at the Kola Peninsula (marked 'Cola' on the map), they were met by local Sámi, along with the captain of the expedition's sister ship, Jan Cornelisz de Rijp. Trying to decipher exactly where they had landed, the crew showed a map to the locals, who were quickly able to help orient them for the journey home to Amsterdam.

©National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London [BHC0359]. Public domain.

Of the original expedition crew, only 12 men made it back to Amsterdam alive. Sadly, Barentsz died during the perilous journey, and djoeke suggests it was likely a combination of scurvy and exposure to the elements.

This painting, Death of William Barentsz, 20 June 1597, is by Christiaan Julius Lodewijk Portman (1836). In the image, he is clutching a map - we wonder if it is a copy of the very map djoeke has chosen for the podcast!

This beautiful map was published in 1598 in Amsterdam by one of the leading publishers of maps and travel books at that time, Cornelis Claesz.

One of Claesz’s most famous works was 'Itinerario' (1596), written by the Dutch merchant and spy Jan Huygen van Linschoten. Coincidentally, Claesz accompanied Barentsz on his first and second voyages! During those journeys, he would have gained access to vital information from Barentsz, Linschoten and other merchants.

djoeke explains to Jerry that a world of information can be gleaned from the features on this early map, including with regard to how information was accumulated. Specifically, maps such as Barentsz' illustrate how knowledge was managed by publishers in Amsterdam, who decided what was shared and what was withheld (sometimes due to governmental decree). She also highlights how the blank areas and uncertainties on maps acted as the catalyst for Europeans to 'discover' new territories and try to create a more complete world view.

Celebrated map of the Arctic from Gerard Mercator's Modern Atlas, Atlas sive Cosmographicae Meditationes de Fabrica Mundi et Fabricati Figura (1595) ©The Sunderland Collection

The core of the geography presented on Barentsz's map was based on the work of Gerard Mercator, and using first hand knowledge from Barentsz's own voyages in the Arctic in 1594 and 1595. However, both Mercator's and Barentsz's maps featured landmarks that were later proven to be incorrect.

©The Sunderland Collection

One such mistake are the mythical islands of Estotiland (west of Greenland) and Friesland (southwest of Iceland), both supposedly discovered by Venetian explorers Nicolò and Antonio Zeno in 1380. These phantom islands were copied onto maps for nearly a century! You can see Friesland here on Girolamo Ruscelli's influential 1561 map of the North Atlantic.

Another common error is located in the east of Barentsz's map: the "Estrecho de Anian," or Strait of Anian, which was believed to be the fabled Northwest Passage. This continued to be included on maps well into the eighteenth century, and the mysteries of the Northeast and Northwest Passages would remained unsolved until 1879 and 1906, respectively.

Olaus Magnus's 'Carta Marina' (1539). Credit: Plymouth Marine Laboratory, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

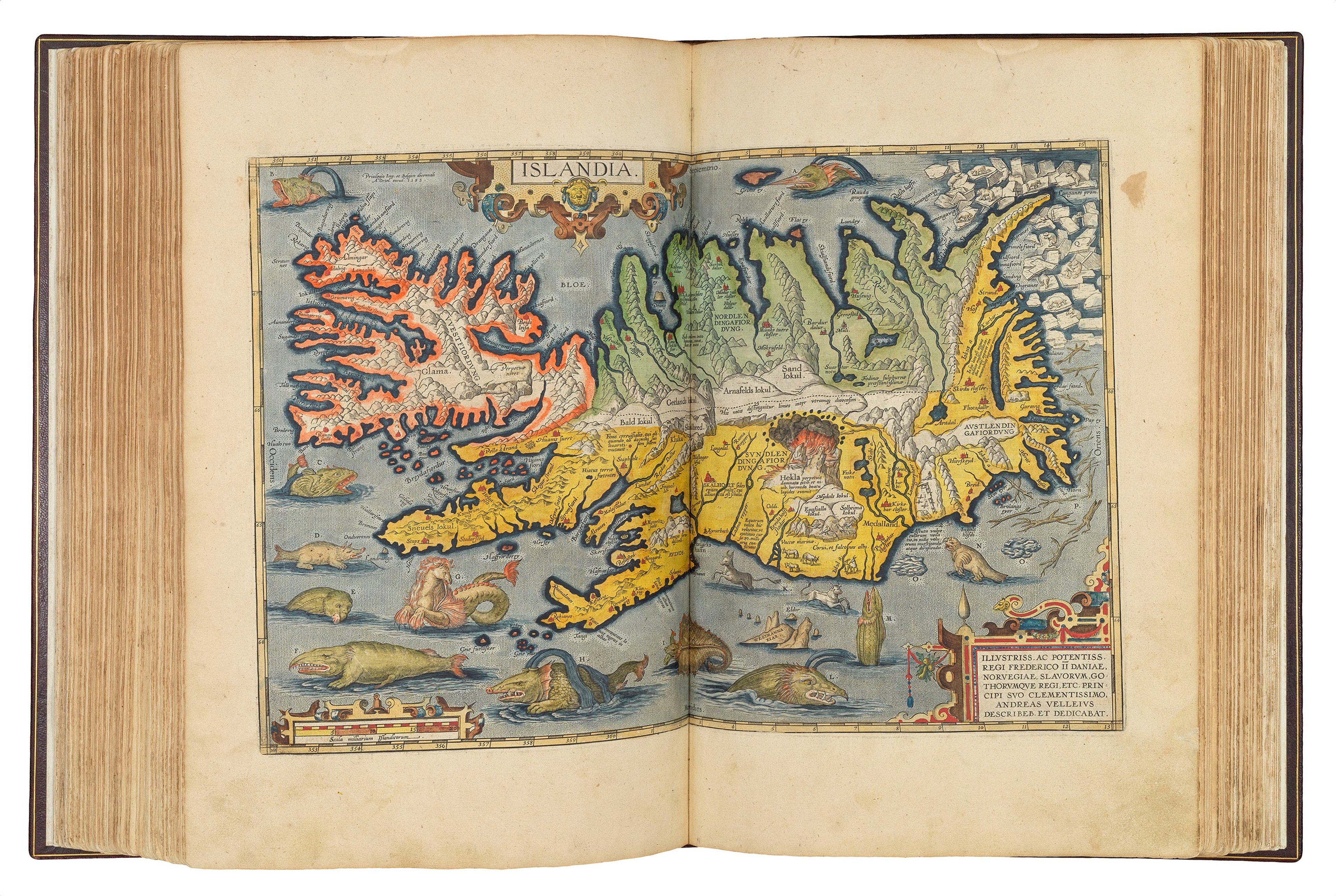

Ortelius' famous map of Iceland (1603) ©The Sunderland Collection

The depictions of animals and sea monsters by Berentsz most likely were influenced by earlier 16th century maps, such as those by Olaus Magnus and Abraham Ortelius, pictured above. Polar bears can be found on both of these works, balancing on the ice floes to the northeast of Iceland. You can find out more about the derivation of sea monsters in our article on Sebastian Münster's Sea Monsters.

About djoeke van Netten

djoeke van Netten ©Harry Otto

Dr djoeke van Netten is an Associate Professor Early Modern History at the University of Amsterdam. Her teachings span world history, military history, and the history of cartography.

She received her MA in History from the University of Groningen (cum laude) in 2004 and completed her PhD in ICOG/History at the University of Groningen in 2012. In 2022, djoeke was the Guest Editor-in-Chief of the Women's History Yearbook. She was also the editor of the Mapping Uncertain Knowledge Special Issue of the Journal for the History of Knowledge in 2024.

djoeke works at the crossroads of the history of knowledge and maritime history, with a deep interest in the history of printed books and maps. She has researched and published several articles on secrecy and openness, especially within the early Dutch East India Company.

djoeke has also worked closely with the National Maritime Museum in Amsterdam as a research fellow, a guest curator and tour guide. In recent years, she has addressed issues such as gender at sea and mapping uncertain knowledge. She is currently researching the role of animals on maps.

Willem Blaeu, by Jeremias Falck (c1655-77). CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

When studying for her PhD at University of Groningen, djoeke examined the roles of seventeenth century publishers in the presentation and dissemination of knowledge.

She focused her studies on the life and work of prolific Amsterdam publisher and Dutch East India Company (VOC) cartographer, Willem Janszoon Blaeu.

Blaeu map of the Arctic (1663), complete with polar bear ©The Sunderland Collection

Why not continue your exploration of the wonderful world of maps by subscribing to the podcast? That way you will never miss an episode.

Feel free to let us know - What's YOUR Map?!